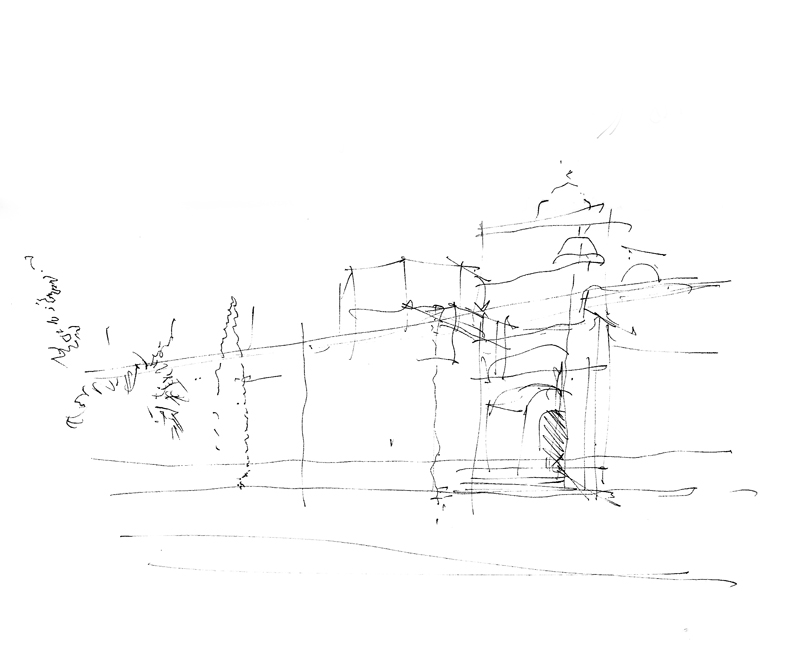

After a brief hiatus, I am continuing my series of views of the Fremont neighborhood of Seattle. At the northwest corner of Evanston Avenue North and North 34th Street sits the Red Door Ale House atop a concrete parking garage. How did it get here?

The original structure was erected on the Fremont tide flats in 1900, before the Lake Washington Ship Canal was constructed. Three years later, it was moved to the northeast corner of Fremont Avenue North and North 34th Street. In 1917, the structure was raised up on stilts so that it would be level with the newly raised streets surrounding it, where it became a familiar sight as one drove across the Fremont Bridge. Originally a drugstore, it was transformed into a tavern in 1938. It is said that the original uneven floor was a sort of sobriety test for those who might have imbibed a little too much ale.

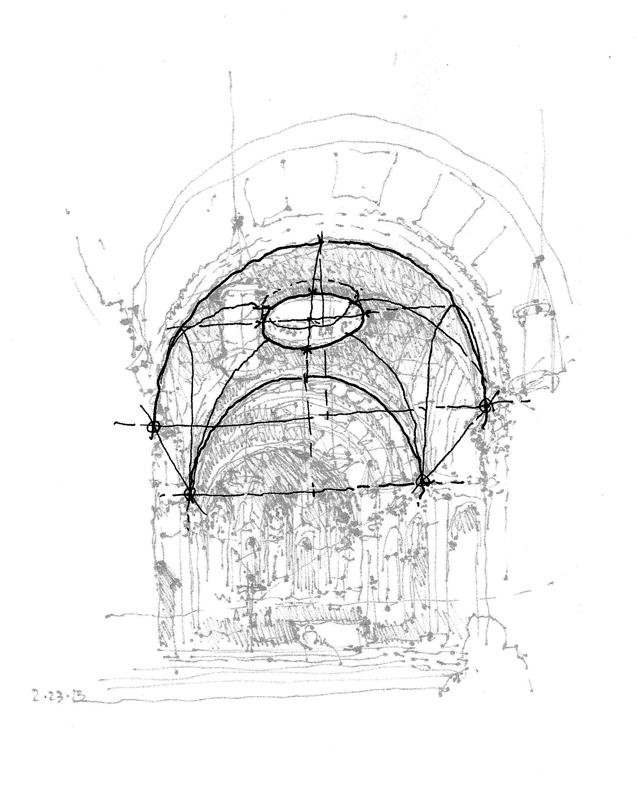

In 2001, to make room for a new mixed use development, the Red Door was relocated to its current location, which you can see in the view above. To the right is the local PCC Natural Market and in the background beyond you can see the Fremont Rocket.