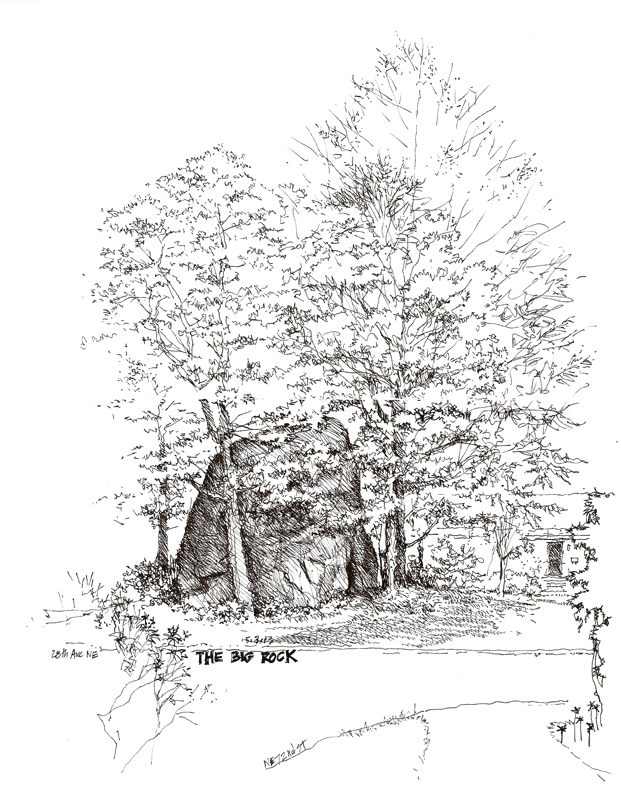

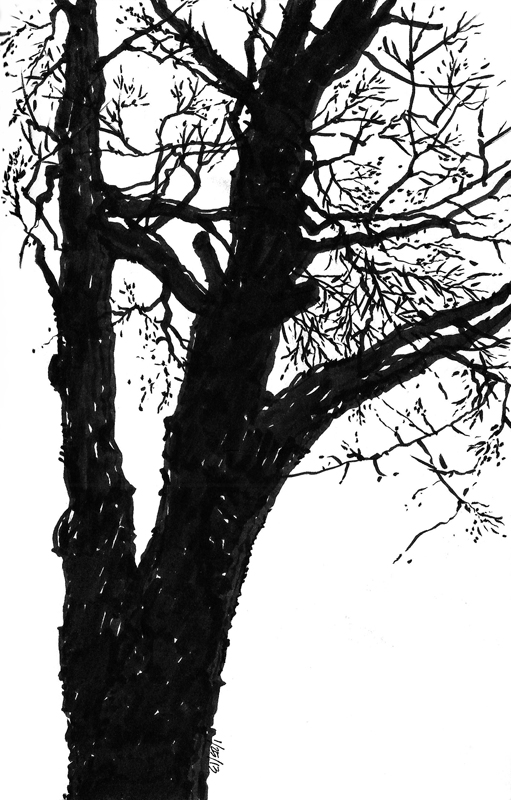

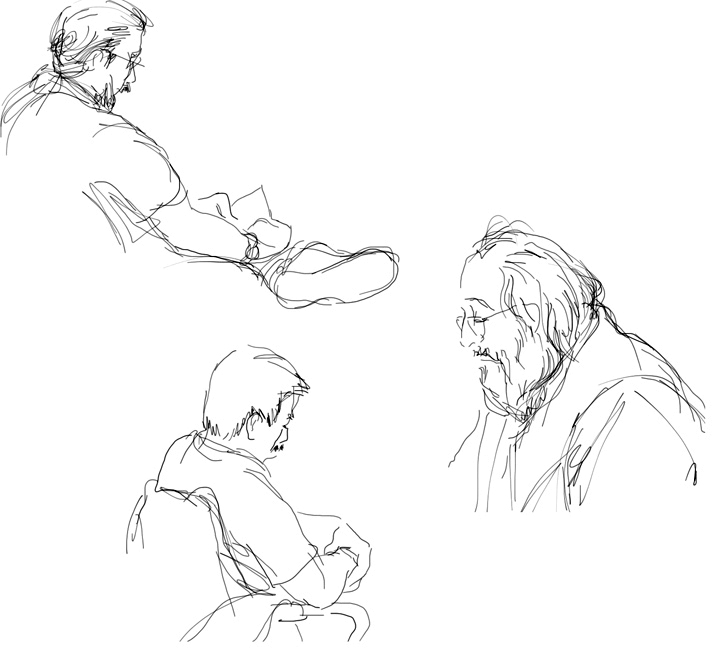

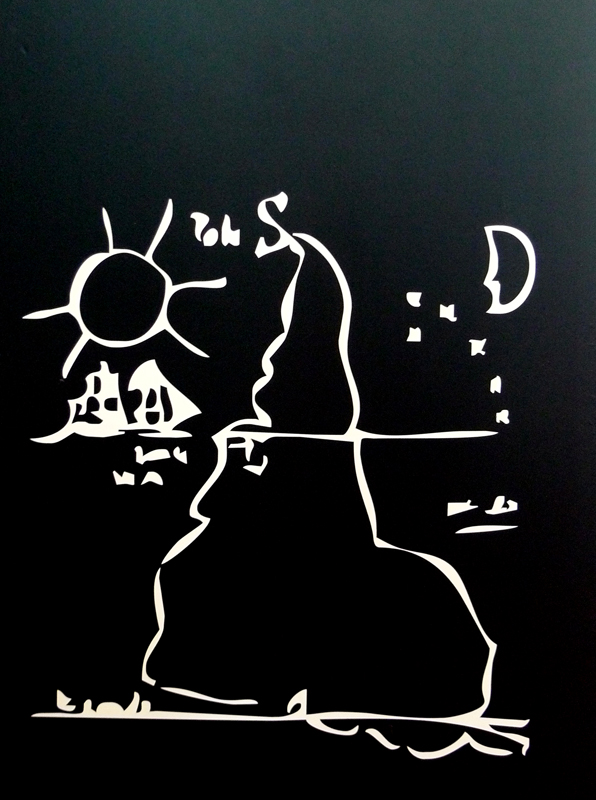

In the Wedgewood neighborhood of north Seattle sits this massive rock measuring 80 feet in circumference and 19 feet in height. Geologists call it a glacial erratic, meaning that its composition does not match its present surroundings. It was deposited more than 14,000 years ago by the Vashon Glacier. As the ice sheet moved inexorably from the north into the Puget Sound area, rocks, sediments and boulders such as this one were carried along by the glacier, and then were left behind when the ice retreated. Originally known as the Lone Rock when it was part of a large farmstead, this large mass is now called simply the Big Rock. It became part of a subdivision platted in the 1940s, where it remains surrounded by houses, trees and brush at the corner of 28th Avenue NE and NE 72nd Street.

This is a weird drawing in the sense that we can’t immediately recognize the Big Rock for what it is. What is that large mass of darkness? We have this yearning to know and identify what it is that we see, which is more easily satisfied when we draw buildings, people, trees and other recognizable things.