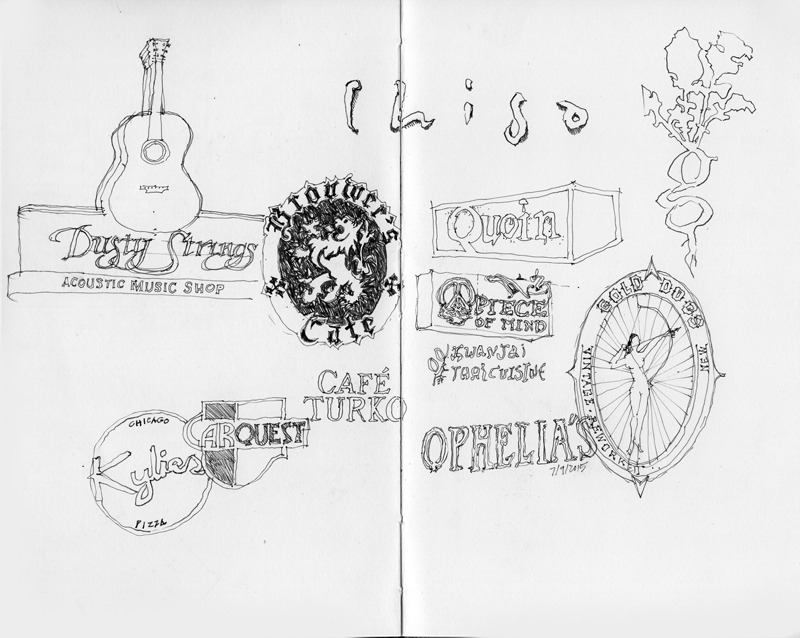

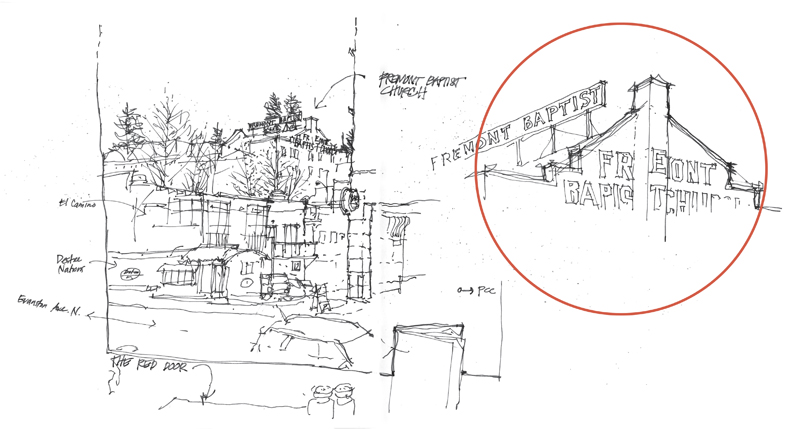

Continuing from a previous post from this past January, these are more signs of Fremont. While I am concentrating on those of places with a history here, a few relative newcomers have probably snuck into the picture. In drawing these, I am struck by the subtle differences in typography that we normally do not notice but which convey the character of a place

Category Archives: Seeing

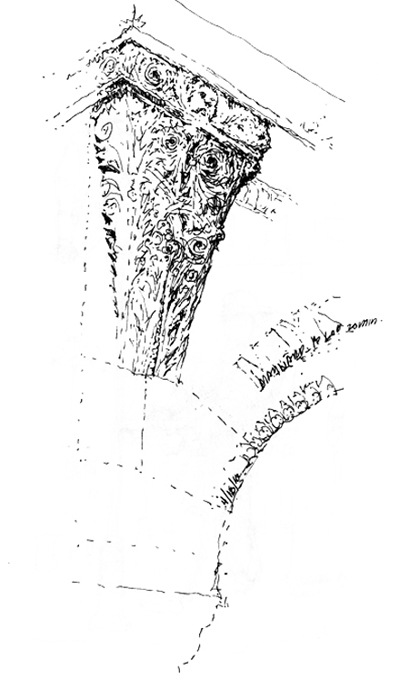

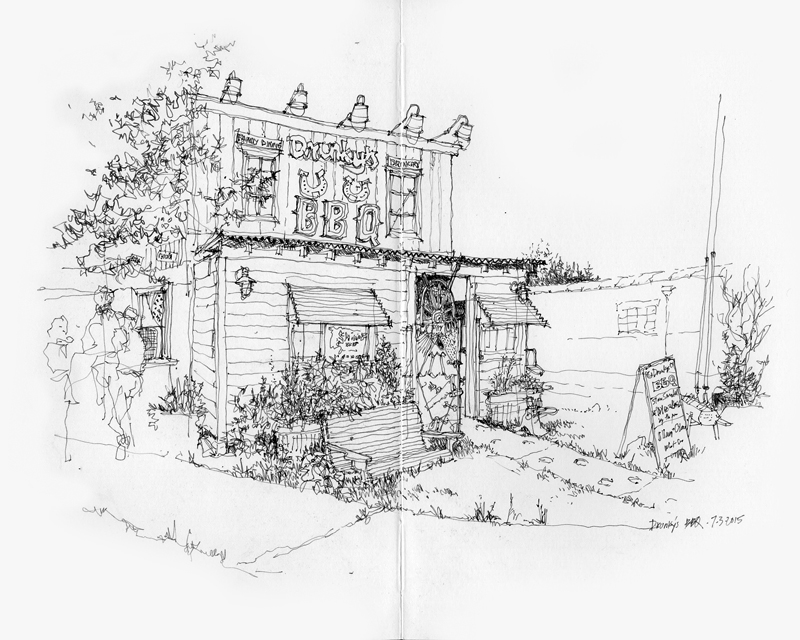

Drunky’s Two Shoe BBQ

A recent addition to the Freelard neighborhood is this BBQ joint at 4105 Leary Way NW. Even though the scene contains a lot of detail, I find that picturesque places like this are easier to draw since slight errors in proportion are much less noticeable than when drawing examples of classical architecture, which followed certain principles of proportional relationships. For example, drawing the Tempietto in Rome was a real challenge. Notice the comment that I wrote after finishing—A little too tall… I had exaggerated the height of the structure just a bit too much.

A recent addition to the Freelard neighborhood is this BBQ joint at 4105 Leary Way NW. Even though the scene contains a lot of detail, I find that picturesque places like this are easier to draw since slight errors in proportion are much less noticeable than when drawing examples of classical architecture, which followed certain principles of proportional relationships. For example, drawing the Tempietto in Rome was a real challenge. Notice the comment that I wrote after finishing—A little too tall… I had exaggerated the height of the structure just a bit too much.

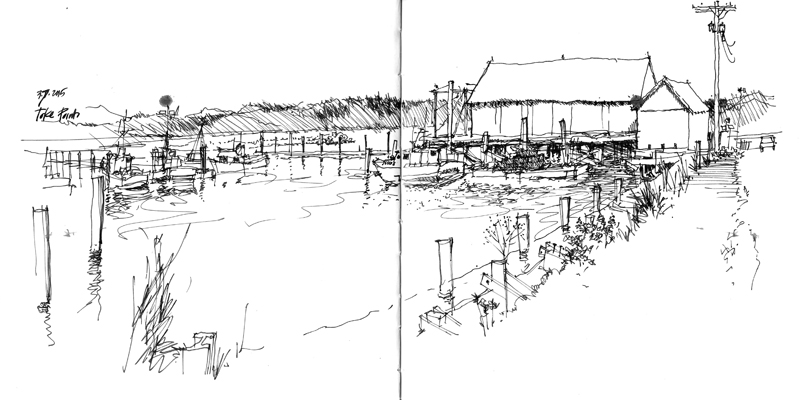

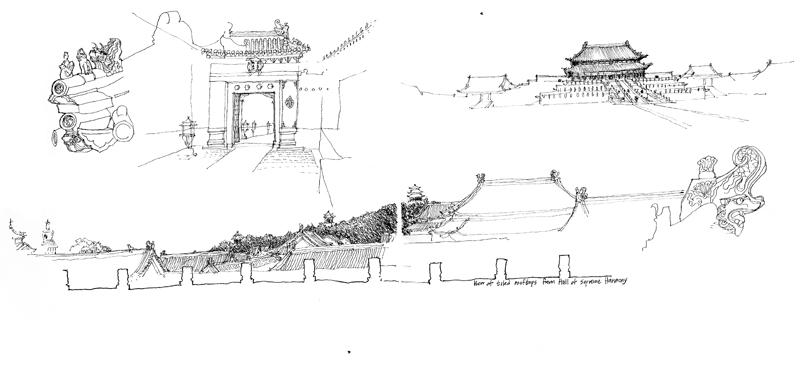

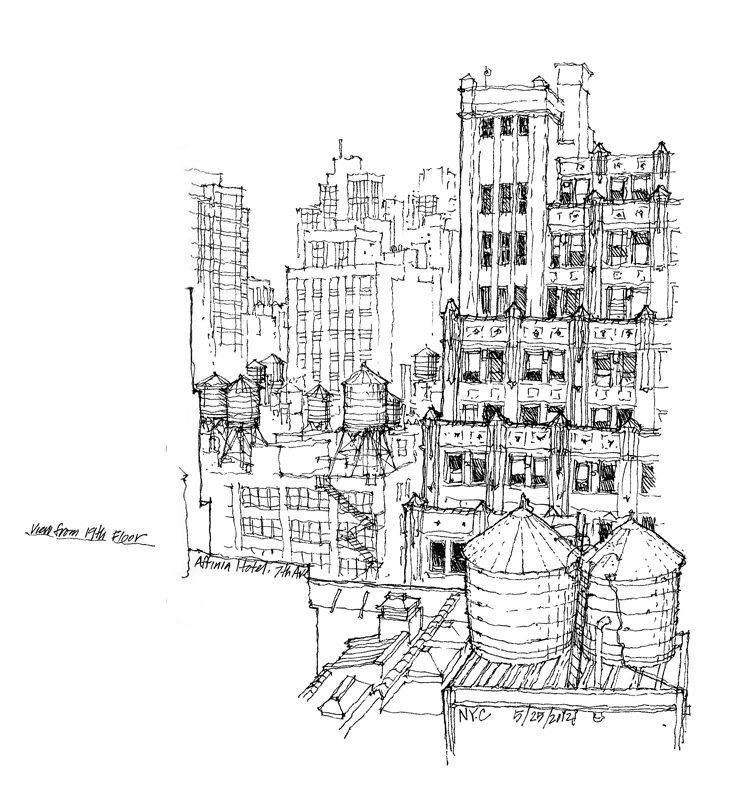

Wide vs. Close-Up Views

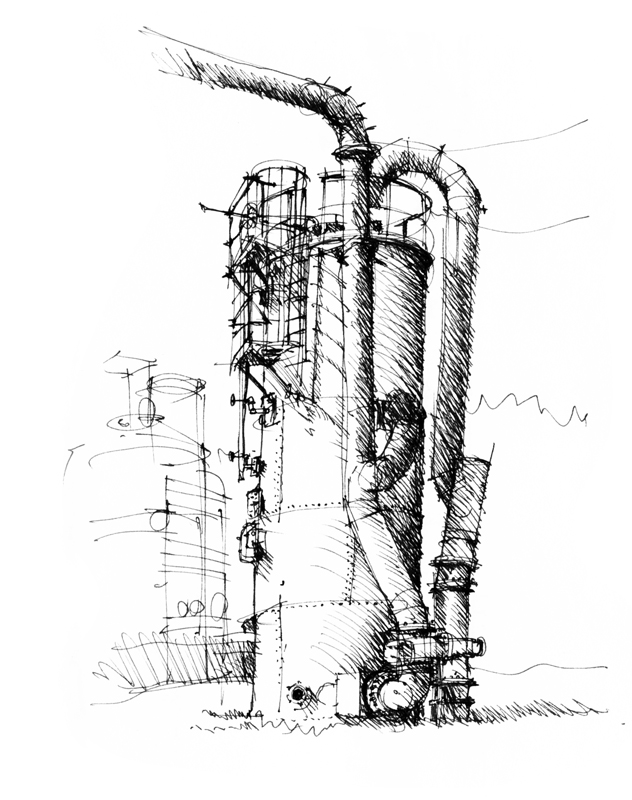

I have always preferred taking photographs with a wide-angle lens—a 35 mm, 28 mm, or even a 24 mm fixed lens. This preference shows up in the views I usually select when drawing on location. My inclination to include context and information in my peripheral vision often leads to panoramic views or perspectives that stretch beyond the classic 60° cone of vision for linear perspectives.

Some photographers prefer the more tightly composed shots made possible with telephoto lenses, which can be seen in how they might frame and compose their on-location drawings.

For those who prefer the flexibility of a zoom lens, the choice of subject matter can suggest how it is to be framed, whether it is a panoramic cityscape or a tighter close-up of a building fragment.

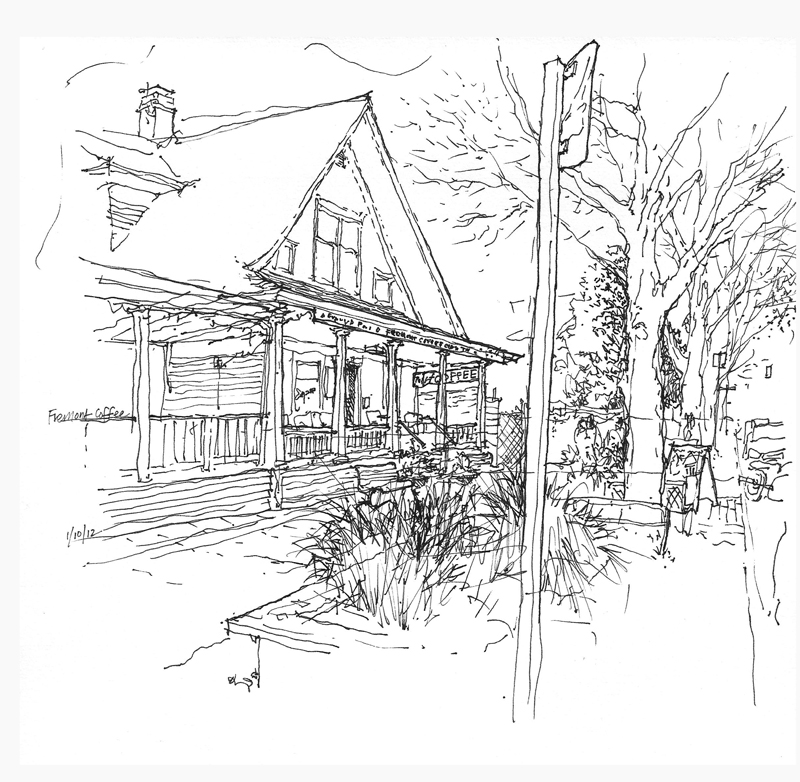

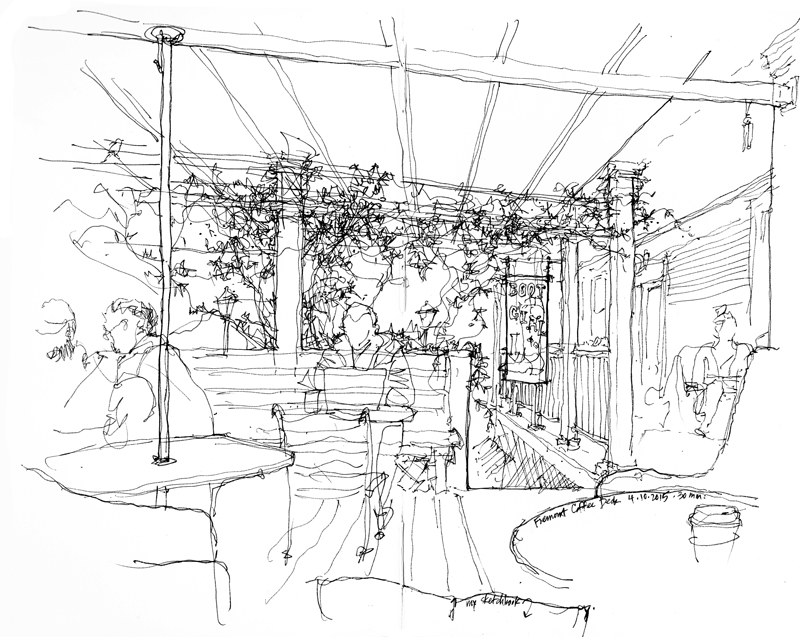

Fremont Coffee Redux

I took advantage of an ad hoc meeting of the Seattle Urban Sketchers at Fremont Coffee to sketch my favorite coffee shop, where I get my daily Americano. Above is an exterior view that I had done a couple of years ago. So today, I sketched two additional views, one of the interior and the other of the outside deck. I had a little trouble conveying the scale of the two spaces. Scale—in particular, human scale—is a difficult aspect to capture well but it is so important in describing the intimacy or expansiveness of a space.

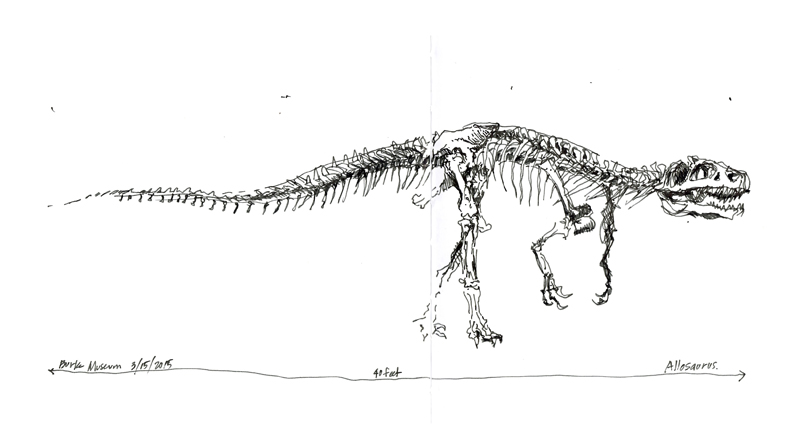

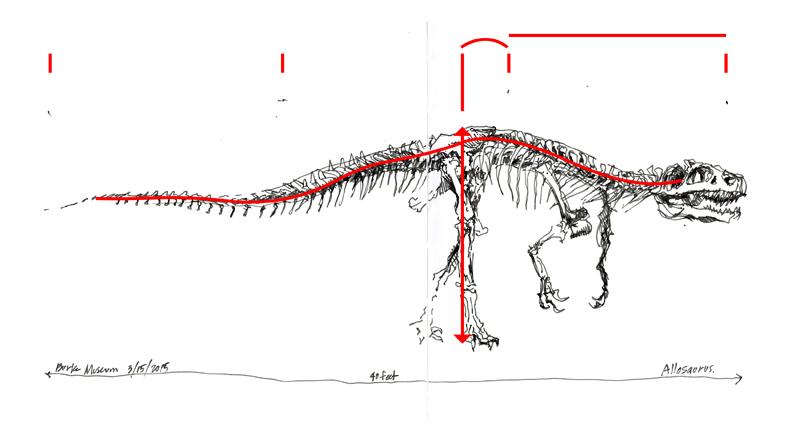

Allosaurus Fragilis

On display at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture on the UW campus is this Allosaurus Fragilis, a fleet-footed predator from the late Jurassic period.

The second image below shows how I attempted to keep the allosaurus in proper proportion. I first estimated that the height of the hind legs was about a third of the dinosaur’s overall length. You can barely see the tic marks that I used to divide the length into thirds. I then used this measurement to fix the height of the hind legs. I also judged the position of the hind legs to be a little more than a third of the length from the head. Finally, I drew the curvature of the spine to guide the development of the dinosaur’s skeleton.

Being able to see and replicate proper proportions, no matter the nature of our subject matter, is an important skill in drawing.

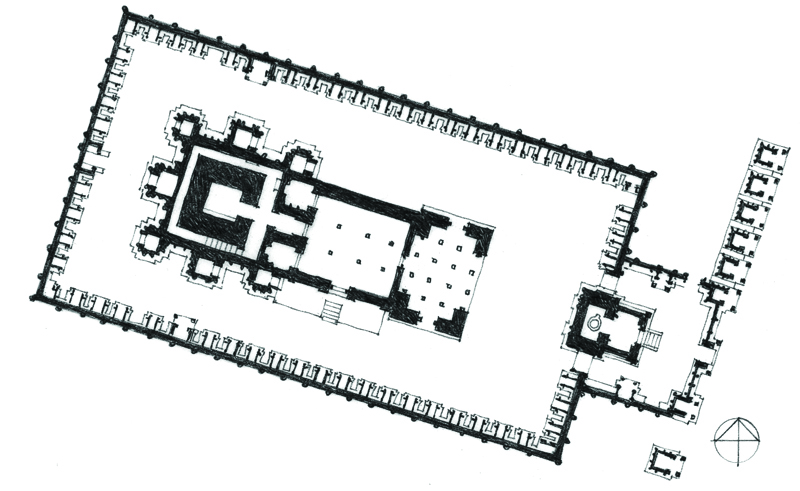

Kailasanathar Temple

At the end of my recent trip to India, Xavier Benedict and I drove down from Chennai to Kanchipuram, where we visited several Hindu temple sites. The most impressive of these was Kailasanathar Temple, the 7th-century Pallava shrine dedicated to the god Shiva. The sandstone structure has weathered over the past 1200 years but is being restored and retains its tiered, sculptural elegance.

While one can read descriptions, study drawings, and pore over photographs of architecture, nothing can compare with actually visiting and experiencing a place. The sights, sounds (or lack thereof), and sense of scale immediately become apparent upon entering. There is no need for any intermediary material. At the conceptual level, however, plans and sections do offer views that can explain the formal layout of a place.

It is Interesting to note the disparity that often exists between reality and how it may be represented. For example, after my visit, I noticed that the plan of Kailasnathar that I had drawn a few years ago is missing columns on the west entry porch.

While I could appreciate the formal order of the temple compound and the artistic expression of the stone carvings, I also realized that not fully understanding the Hindu iconography prevented me from truly appreciating what I was experiencing.

Pike & Minor

Despite recovering from a bad cold and feeling a bit under the weather, I decided to join the monthly Seattle Urban Sketchers outing this past Sunday. It promised to be an unseasonably warm and sunny day but it was still quite chilly in the late morning when I drew this view of Pike Street in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle, standing in front of the new Starbucks Roastery, looking east toward the domed First Covenant Church. Not my finest work but merely another step in the long process of learning how to say more with less. There is so much missing in this drawing, so many things that I saw but omitted, and yet, the overall feel for that particular place is still there.

Iconic Images

If we think of the Eiffel Tower, the Sydney Opera House, or the Chrysler Building in New York City, we can see the image in our head, even if we have never seen the real thing. It appears as though the stream of images we have seen in photographs and movies have been seared into our memory banks. And we might even be able to sketch reasonable facsimiles if asked to.

After we have visited a place several times, or lived near to, driven by, or walked past a place for a number of years, we might also form an iconic image of that place. A personal example is the Fremont Baptist Church, established in 1892 with the current brick building being constructed in 1924, perched on a hill above downtown Fremont in Seattle.

For me, this iconic image of Fremont has materialized over the years. Yet the image I hold in my mind’s eye does not correspond to what you can actually see from any position on the street. What seems to occur is that our mind is able to recombine the fragmented, partial views we’ve experienced into a single iconic, memorable image.

About Copying

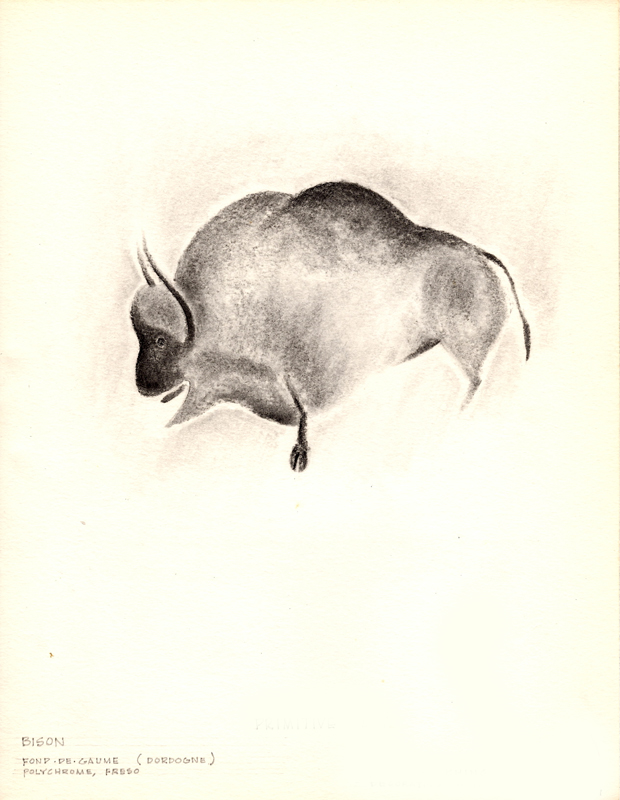

Back in 1963, an art history course at the University of Notre Dame required me to copy a number of art works. The idea was to supplement the reading about and viewing of art with the act of reproducing art. Here are three examples from my course notebook that I happened upon recently.

Dordogne Cave fresco of a bison

Dordogne Cave fresco of a bison

Veronese’s Head of St. Mennas (detail)

Frans Hals’ Young Flute Player

It had long been a tradition in the studio arts to copy masterworks as a way to gain proficiency, the thinking being that one could learn by imitating the compositional strategies, the strokes and blending of colors, and other techniques used by artists more skilled than ourselves. There are art teachers, however, who consider this type of copying to be a crutch and an obstacle to developing one’s own creative mind. Whether the practice of copying is good or bad depends ultimately on the reasons for doing so. The motivation for copying should not be merely the reproduction of a work. Rather, it should be seen as an attempt to explore the process of the original artist and just a single step in the learning process.

I should point out that drawing on location neatly sidesteps the question of copying. But note that even here, we are in a sense copying what our visual system takes in and interprets.

Surface and Depth

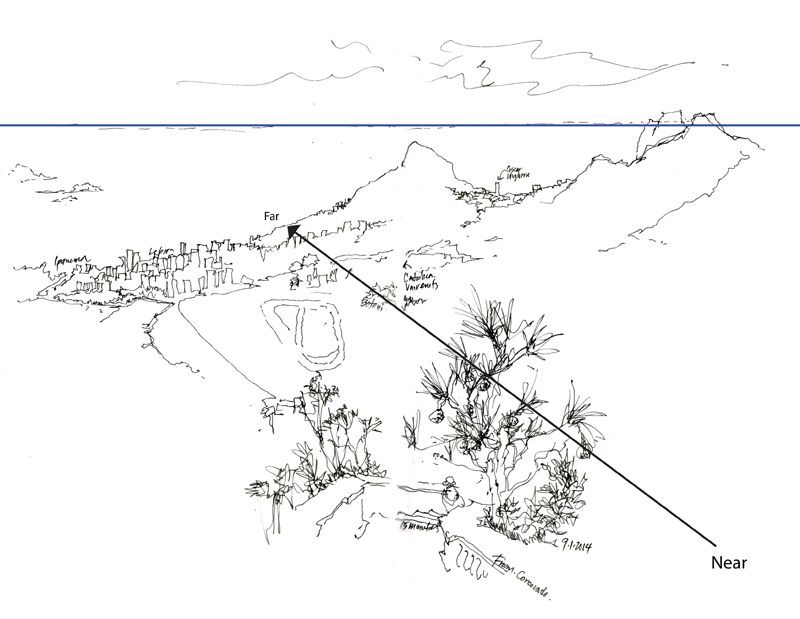

In the 1950s, the psychologist J.J. Gibson outlined a number of cues to depth perception. A few rely on our binocular vision and therefore do not apply to 2-dimensional drawings and paintings. Others, however, are psychological rather than physiological in nature. As such, these depth cues are pictorial in nature and are applicable to drawing and painting on a 2-dimensional surface. In the following, I try to use simple terms and snippets of my own drawings and photographs to illustrate each of the depth cues that I consider to be relevant to drawing on location.

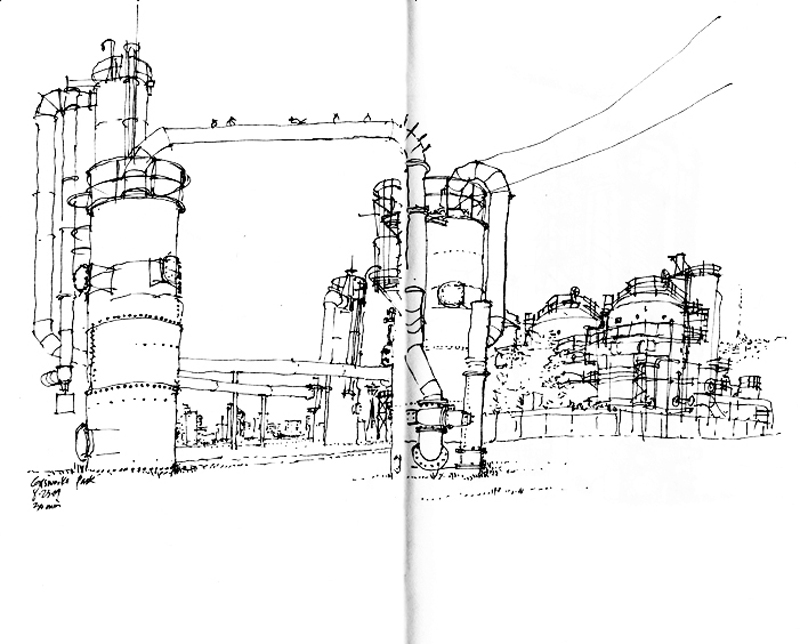

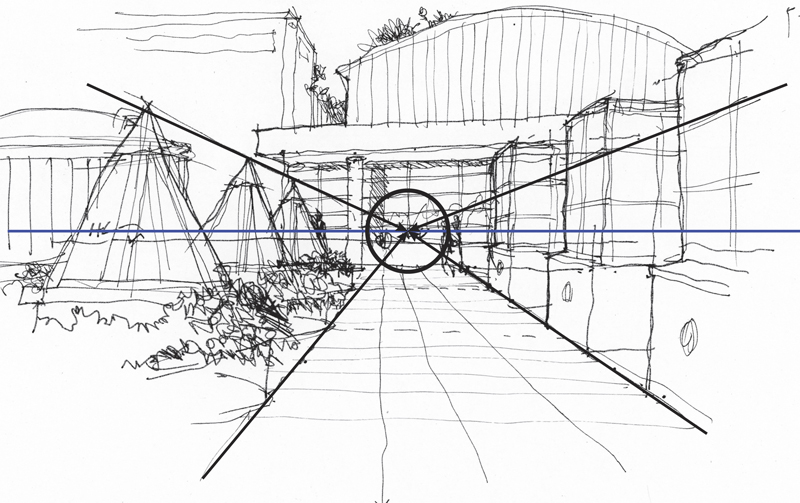

Convergence of parallels: This is a key characteristic of linear perspective in which parallel lines appear to converge as they recede into the distance. Despite the usefulness of the other depth cues, linear perspective remains the structural scaffolding upon which to build a sense of spatial depth on the page.

Overlap: Near objects overlap or partially block the view of objects farther away. Locating effective overlaps can be useful in selecting a viewpoint and composing a drawing.

Position relative to the horizon: Objects below our eye level rise toward the horizon as they recede; objects above our eye level descend toward the horizon as they recede.

Relative size: Objects known or assumed to be of similar size appear to shrink in size with distance from the observer.

Texture gradient: Surface texture appears to get finer and smoother with distance from the observer.

Shading and shadows: Contrasts in light and dark can convey the shape, form and depth of objects.

Aerial perspective: Particles in the atmosphere affects the color and visual acuity of objects at varying distances from the observer; distant objects appear grayer or bluer and less distinct than nearer objects.

As we can see, scenes more often than not comprise a number of these depth cues operating simultaneously. Seeing how these depth cues occur in our real-life perception can aid our understanding of why things appear as they do, counter to what we know of the things we draw, which are often in conflict.