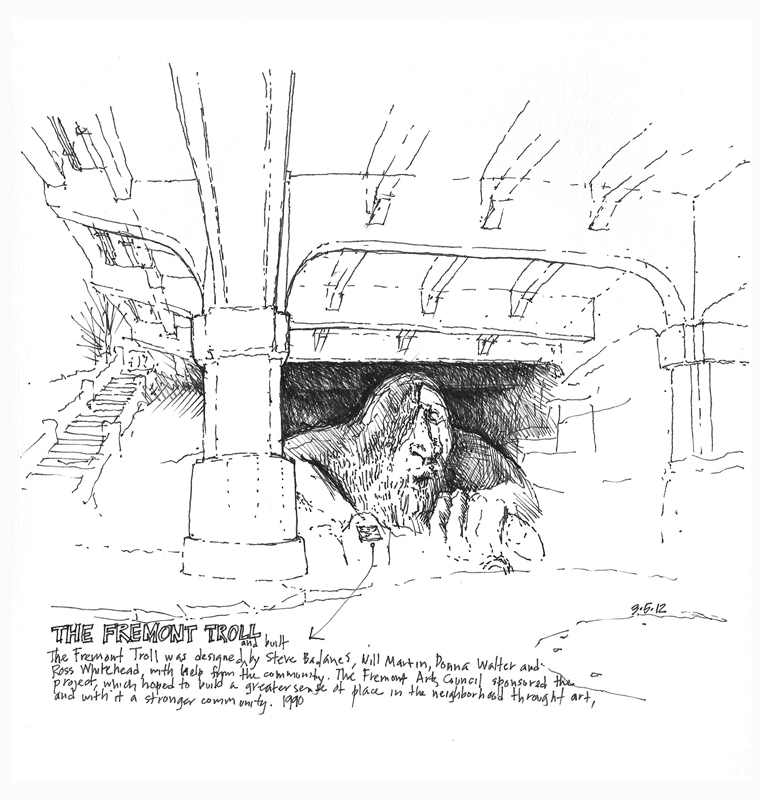

Last week I met up with Frank Bettendorf, a fellow urban sketcher from Mount Vernon, and spent a few hours roaming around Fremont looking for sketching opportunities. While this was intended to be a sketching session, we ended up talking more about drawing rather than actually placing pen to paper. Frank B. had a lot of questions, and good ones too!

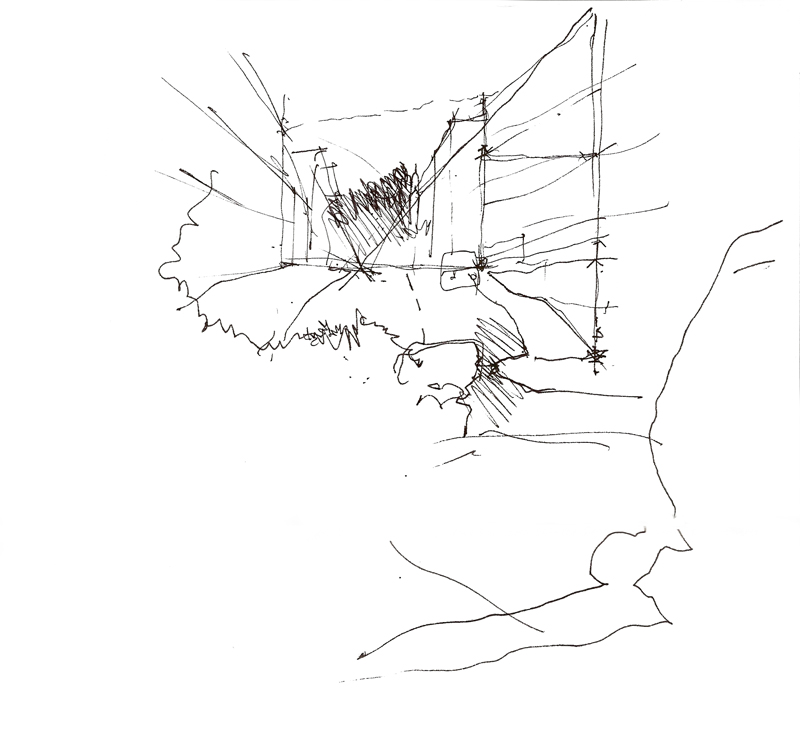

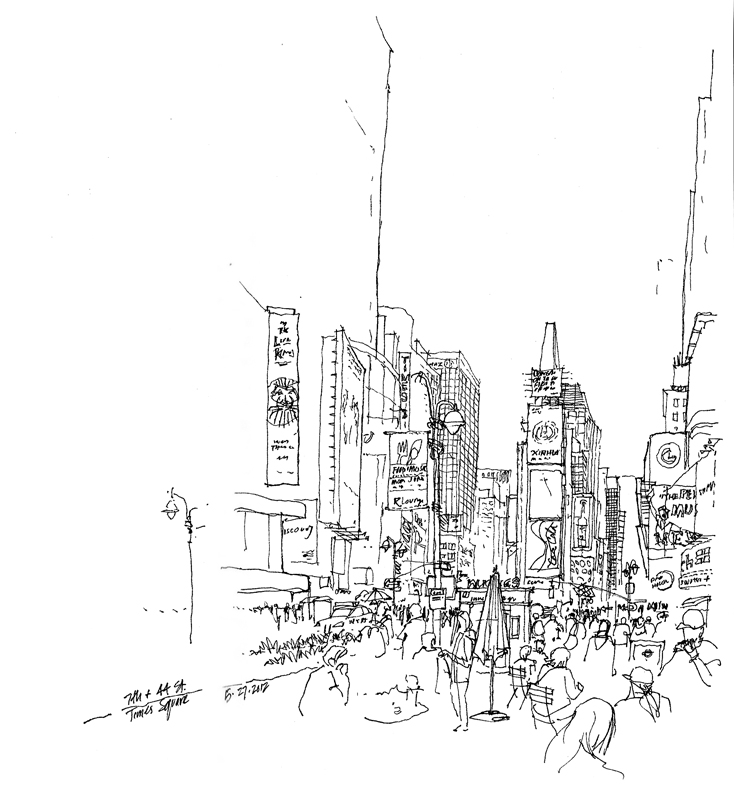

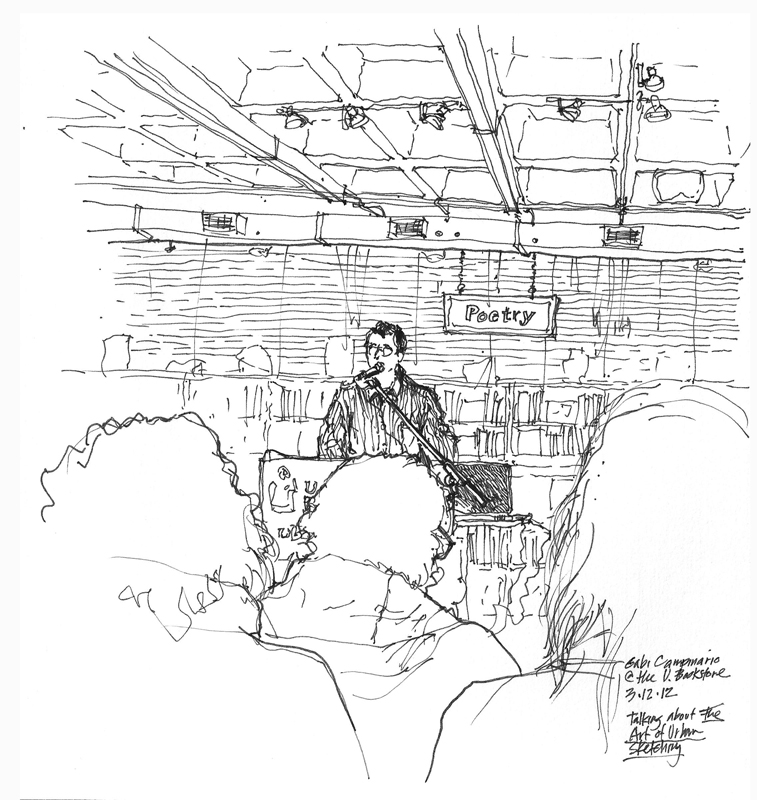

Having to explain my approach, the sequence in which I work, and how I make certain decisions along the way—all of these particulars made me realize how much I take for granted when I draw. It was useful to have to clarify and rationalize how I draw. Above is one of the sketches I used to explain my process.

I also recognize now that while many people might admire a finished drawing, the process by which it came to be can remain an inscrutable process, shrouded in mystery. Some of the keys I put forward are: composing the view by selecting an appropriate viewpoint; envisioning the scope of the drawing and placing it mentally on the page before laying down a line; starting strategically with a few key lines to establish the overall structure of the drawing; and thinking about how to convey the layers of spatial depth we see. This last point is probably the most important key: learning how to see.

And in exchange for spending a few delightful hours with Frank B., I got a free lunch at Tacos Guaymas! I look forward to more drawing sessions with Frank B.